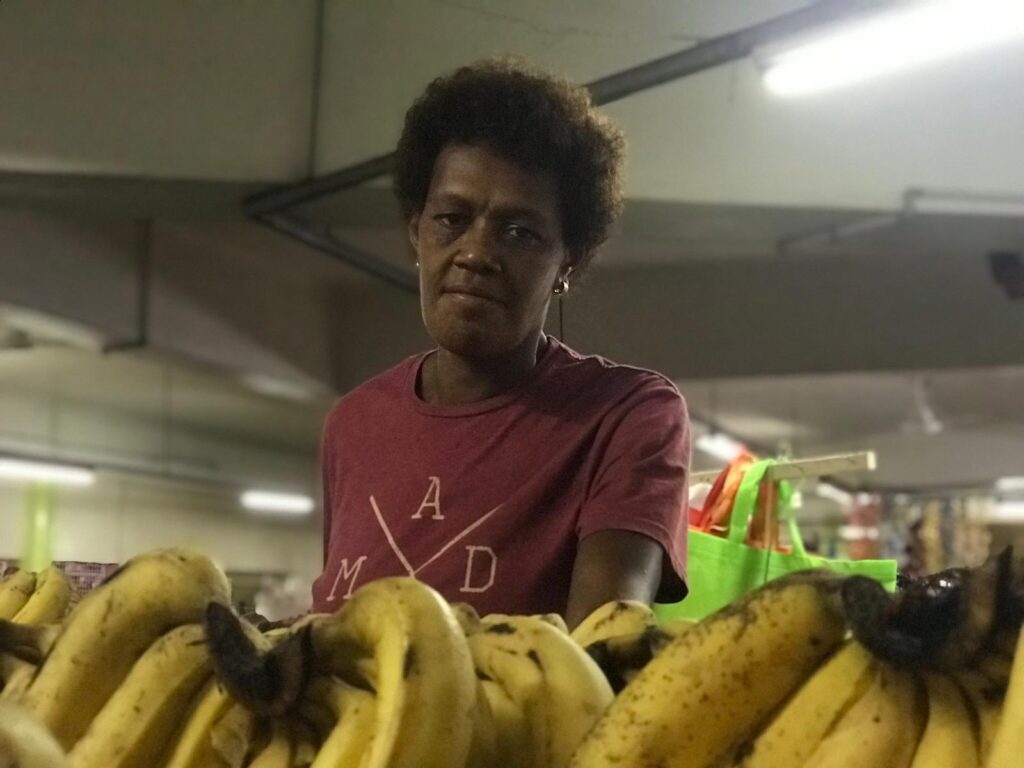

Unaisi Latinacolo has huge responsibilities on her shoulders and in the last couple of years, she’s had to lift those burdens alone.

But the faith her husband had on a crop that is pretty much forgotten in Fiji, gave Una a source of income when he couldn’t be there to provide for the family.

The 44-year-old mother of five lives in Lomaivuna in the highland province of Naitasiri, a region which 60 years ago was the scene of a thriving banana industry.

The industry declined following the emergence of a fungus called the Sigatoka Black Leaf disease which kills leaves and leaves fruit hanging without reaching full maturity.

The disease stopped what at the time was the second highest agricultural export commodity from reaching full potential.

Many years after the decline of the Banana industry, a few people continue to earn a living from the fruit.

Foresight provides for tough times

Una’s family’s 300 tree plantation, started more than 20 years ago by her husband, is a tiny throwback to the industry which once made Lomaivuna the focus of Fijian agricultural attention.

With school supplies, daily food needs, weekly cooking duties at her children’s boarding school and a household of extended family to look after, Una’s life looks hard.

When the one-hour walk each way to her mountain farm is factored in, Bananas do not seem so attractive a commodity, but Una’s bananas are always sold out every Saturday and so she calls it ‘easy money.’

“Every Monday, I start my day very early, sometimes around 4am to prepare my children’s breakfast and send them off to school because I then have to prepare myself for the day.”

The path to her banana plantation is muddy and wet, and the further up the walk, the more moisture she will encounter. Bananas thrive in the wet, warm humidity of the tropics so her husband had to go deep into virgin forests to begin their banana ‘empire’.

“The walk to the farm is easy but on the way back it’s very hard because I have to climb several hills and mountains with my sack of banana on my back. And I can’t be lazy, I have to manage my time well because that is usually the day I have to go and cook lunch for all the children in my kids’ school.”

Banana farmers harvest the fruit at the beginning of the week so they can be carted to the capital city, Suva to a ripening facility where they will spend the rest of the week.

Farmers from the province of Naitasiri provide much of the fresh produce sold in Suva and at the market in nearby Nausori town, so every weekend Una is one of hundreds of vendors, most of whom are women, who make their way down to sell fresh produce in Suva.

While the common crops are leafy vegetables and root crops, Una’s bananas are always sold out, a testament of information confirmed by Fiji’s Ministry of Agriculture that local banana farmers don’t produce enough for local demand. In fact, according to the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) in December 1961 Fiji produced 8,800.00 tonnes of Banana. In 2018, it was down to less than half of that. Not even enough for exports.

Una only has time and energy to cut between 2-3 sticks of bananas which has enough hands of the fruit to fill one and a half crates.

The single full crate she sells almost entirely at wholesale price to another woman vendor at the market at Nabua, a suburb between the towns of Nausori and Suva. It is an arrangement the two have had for a while that works for them. The leftover hands of Banana, Una may retail for extra cash.

Given their subsistence lifestyle, the $80 she makes is enough for a rural Fijian family to pay for the week’s essentials; salt, sugar, oil, medicine and some bread for the Sunday breakfast. Una even has a little bit left over to save for a rainy day.

She could harvest more and earn more cash but she is alone, not only because her husband is in jail but also because there is very little infrastructural support for the fruit. Fijian government agronomists who gave background information about the industry admitted not enough research or support for markets currently exist in their plans. However, international support for the region’s main development agency the Pacific Community (SPC) has changed that.

“Even though my husband is away, I am able to provide from the fruits of his hard work and we are able to live comfortably. I am looking forward to his return because I only have enough time to harvest but I must also clean the plantation and prepare for replanting.”

“Bananas thrive when you keep the plantation clean and clear but you must also know how to cut the bunch so that the fruit grows healthy.”

“This is something he usually does.”

Keeping banana plantations clean, planting the banana trees a particular distance from each other and paying banana sticks tender loving care can result in longer lasting beautiful bananas, traits which are necessary for when the fruit has to travel to far off export markets.

Most Fijian fresh produce suppliers like Una plant on tribal land which don’t have access roads so unlike in South America, South East Asia and China, the other major exporters of Banana, in Fiji, farmers of this particular fruit still have to do much of the work manually.

A way forward

Agronomists at the Fijian government say cluster farming, banana management, technical support and sustainable agricultural practices could change the way bananas make money for farm to table producers like Una.

Una suggested the local Ministry of Agriculture extension office at Lomaivuna, a couple of kilometres down the road from her could support farmers by improving access roads to tribal lands and getting them plant materials.

“It is an easy income for me, Bananas grow easily up here but if the government can help us with clean plants, we can get more bananas and less will be damaged. Right now I just do what I can.”

A partnership between the Australian Government and SPC could be the answer to a disease ridden industry.

Facilitated by the Australian government’s Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), the partnership means the Pacific’s only gene bank, the Centre for Pacific Crops and Trees or CePaCT, take plant samples from major cash crops of the islands which are then cultivated to be resilient and disease free.

Banana is also a valuable commodity of the Australian state of Queensland so ACIAR has had an interest in fighting banana disease like the kind that shut down Fiji’s ability to export.

According to the SPC, tissue culture and research funding support given by the ACIAR could provide the local Banana industry and fruit farmers like Una with new life.

This story was supported by funding from the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) and Australian AID as part of the Celebration Agriculture in the News programme.