Patrick D. Nunn, University of the Sunshine Coast and Roselyn Kumar, University of the Sunshine Coast

The storm of climate change is approaching the Pacific Islands. Its likely impact has been hugely amplified by decades of global inertia and the islands’ growing dependency on developed countries.

The background to this situation is straightforward. For a long time, richer developed countries have been underwriting the costs of climate change in poorer developing countries, leaving them reliant on Western solutions to their climate-related issues.

Read more: Their fate isn’t sealed: Pacific nations can survive climate change – if locals take the lead

But as rising sea water continues to encroach on these low-lying Pacific islands, inundating infrastructure and even cemeteries, it’s clear almost every externally sponsored attempt at climate adaptation has failed here.

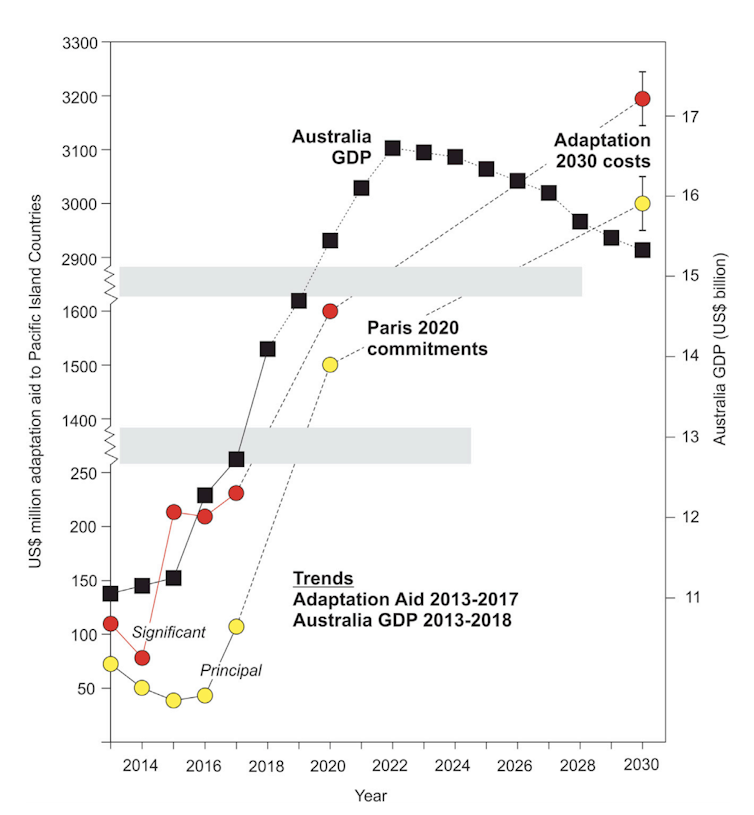

And as the costs of adaptation in richer countries escalate, this funding support to developing countries will likely taper out in future.

We’ve researched climate change adaptation in the Pacific for more than 50 years. We argue this trend is not merely unsustainable, but also dangerous. Pacific Island nations must start drawing from traditional knowledge to adapt to climate change, rather than continue to rely on foreign funds.

Western solutions don’t always work

On a global scale, climate adaptation strategies have largely been either ineffective or unsustainable.

This is especially the case in non-Western contexts, where Western science continues to be privileged. In the Pacific Islands, this is often because these Western strategies invariably subordinate, even ignore, funding recipients’ culturally grounded worldviews.

A good example is the desire of foreign donors to build hard structures, such as sea walls, to protect eroding coasts. This is the preferred strategy in richer nations.

However it does not embrace nature-based solutions such as replanting coastal mangroves, which can be more readily sustained in poorer contexts.

A likely scenario

The availability of external financial assistance means developing countries have become more dependent on their richer counterparts for climate change adaptation.

For example, between 2016 and 2019, Australia provided A$300 million to help Pacific Island nations adapt to climate change, committing to a further $500 million to 2025. This left little need or incentive for these countries to fund their own adaptation needs.

Read more: Pacific Island nations will no longer stand for Australia’s inaction on climate change

But imagine this climate change scenario. Ten years from now, unprecedented rainfall is dumped on Australia’s east coast over a prolonged period. Several cities become flooded and remain so for weeks.

In the aftermath, the Australian government scrambles to make recently flooded areas liveable once more. They build a series of massive coastal dikes – structures to prevent the rising sea from flooding populated areas.

The cost is exorbitant and unanticipated – like COVID-19 – so the government will look for ways to shuffle money around. This may well include reducing financial aid for climate change adaptation in poorer countries.

Plunging international aid

Economic modelling shows nations will incur massive costs this century to adapt to climate change within their own borders. So it’s almost inevitable wealthier countries will rethink the extent of their assistance to the developing world.

In fact, even before the pandemic, Australia’s foreign aid budget was projected to decrease in real terms by nearly 12% from 2020 to 2023.

These factors do not bode well for developing countries, which will be facing higher climate adaptation costs and dwindling foreign aid assistance.

Building autonomy with ‘cashless adaptation’

Leaders of developing countries should anticipate this situation now, and reverse their growing dependence on outside assistance.

For example, rural communities in regions like the Pacific Islands could revive their use of “cashless adaptation”. This means developing ways of adapting livelihoods to climate change that cost nothing.

These methods include the intentional planting of surplus crops, the use of traditional methods of food preservation and water storage, the use of free locally-available materials and labour for constructing sea defences. And it perhaps even includes the recognition that living along coastal fringes exposes you unnecessarily to weather-related change.

Prior to globalisation, this is how it was for decades, even centuries, in places like the rural Pacific islands. Then, adaptation to a changing environment was sustained by cooperation with one another and the use of freely available materials, not with cash.

Researchers have also argued for such “looking forward to the past” strategies regarding Hawaii’s climate adaptation.

And research from last year in Fiji showed more rural communities still have and use a stock of traditional methods for anticipating and withstanding disasters, such as flood and drought.

Read more: Five years on from the earthquake in Bhaktapur, Nepal, heritage-led recovery is uniting community

We can take this argument further. Perhaps it’s time for Pacific Island nations to rediscover traditional medicines, at least for primary health care, to supplement western medicine.

Greater production and consumption of locally grown foods, over imported foods, is also an important and valuable transformation.

The future of the developing world

The need for nations to adapt to unanticipated phenomena like climate change and COVID-19 encourages de-globalisation – including that countries depend less on cross-border aid and economic activity. So it seems inevitable that under current global circumstances, smaller economies will be forced to become more efficient and self-reliant.

Restoring traditional adaptation strategies would not only drive effective and sustainable climate change adaptation, but also would restore residents’ beliefs in their own time-honoured ways of coping with environmental shocks.

This not only means finding ways to reduce costs through cashless adaptation, but also to explore radical ways of reducing dependency and increasing autonomy. An appeal to past practice, and traditional ways of coping, is well worth considering.

Patrick D. Nunn, Professor of Geography, School of Social Sciences, University of the Sunshine Coast and Roselyn Kumar, , University of the Sunshine Coast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.